Gnashing of Teeth

The lessons from the Peace of Westphalia

I’d like to tell you a bedtime story. It’s not one of those enchanting and weird fairy tales in the vein of the Brothers Grimm, but rather one of those synthetic ones with a moral at the end. Children hate those, but up to certain age they’re still too young to recognize the trick. Here’s how it goes.

***

There were good people in the empire, living peacefully side by side. Then, one day, a new religion emerged. Those who embraced it believed that the old faith, once good and just, had been corrupted by the devil, and that its followers would inevitably end up in hell. Those who remained true to the old religion thought that the converts had been deceived by the devil into mocking and despising the one true faith. They were led by sinful pride, and they would, it goes without saying, all end up in hell.

Each side believed not only that the other was wrong, but also that they are straying toward eternal damnation and therefore had to be saved, even against their will, and if persuasion failed, then let it be the sword. For what, after all, is a bit of suffering in this mortal world when eternal bliss is at stake?

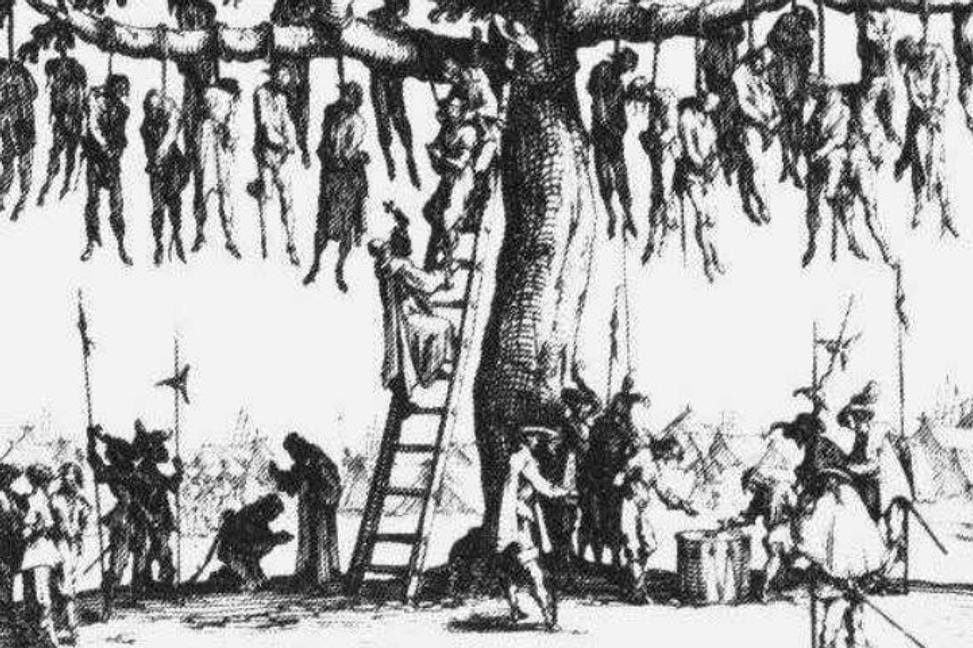

After a century of wars, the empire was half empty. Wild animals roamed where people had once lived. Those who had not perished in battle, in massacres, or during looting, died of hunger or the diseases that go hand in hand with war. Soldiers plundered anyone they could, just to survive. Fields laid barren. Peasants hid in the forests, fearing their own armies as much as the enemy’s.

The warring princes themselves had been driven into poverty by the endless war. At last, they realized there was no way to go on like this. They resolved to make peace. But they hated each other so much that they could not even meet in the same city. Instead, they gathered in two towns, close to one another, and messengers rode back and forth between them until, at long last, peace was forged.

They agreed that from then on, they would leave those of the other faith in peace. They might be wrong, they might be serving the devil, they might be risking eternal damnation, but so be it. Living beside them without meddling in their affairs would demand much gnashing of teeth, yet so be it. It was still better than hiding in the woods, fearing that one’s own army might take everything one had, if it didn’t kill you outright.

And so they lived happily, gnashing their teeth, ever after.

***

That’s, of course, the story of Thirty Years’ War and the Peace of Westphalia. It’s great in that it doesn’t paint a naive, rosy picture of tolerance, where everybody is happy to defer to everybody else. It shows how gnashing of teeth is the prerequisite of achieving a tolerant society. And I love a good parable as much as anyone. But, unfortunately, the story is also to a large extent untrue.

It’s not true that there was no religious tolerance before the Thirty Years’ War. The principle of cuius regio, eius religio (rulers given free hand to choose the religion for their realm) was introduced in the Peace of Augsburg fifty years prior to the Thirty Years’ War.

The conflict has begun, without doubt, as a religious one. Czech protestants tossed catholic governors out of a window. When the governors landed safely on a dung heap, they claimed it was due to the help of Virgin Mary. That’s as religious as it gets. But as the war dragged on, curious things started to happen. Catholic armies recruited protestant soldiers. Protestant armies recruited catholic soldiers. Catholic France joined the show on the side of protestant Sweden. The conflict that once started as a religious war eventually turned into a standard struggle for power.

What im theory looks like an orderly war between two factions was in fact pretty different on the ground. It was a bloody chaos. The troops plundered the civilian population, friend and foe alike. Nobody asked whether you were a Catholic or a Protestant before killing you. Think of the recent civil war in Syria and turn it up to eleven.

It’s not true that all warring parties were fully exhausted by 1648. France, for example, rather figured out that it has better wars to fight (e.g. Franco-Spanish War) than the pointless and never ending conflict in HRE.

The Peace of Westphalia, as already said, hasn’t introduced religious tolerance. It kept cuius regio, eius religio in place, but made some minor adjustments. Most importantly, the rulers could now choose from three options (Catholic, Lutheran, Calvinist) instead of the previous two. It was in no way universalist. One couldn’t adopt, say, Islam or — the horror! — a different, non-sanctioned strain of Christianity.

The tolerance back then was not what we mean by tolerance today. It still worked in pre-modern way. It was granted to realms or groups, not individual people. One’s rights were still linked to the group they belonged to, not to the individual as such. (The story of how we stopped assigning rights to groups, whether social classes, confessions, nationalities, gilds or whatever, is another big narrative that’s never told!)

***

All that being said, the Peace of Westphalia can still teach us valuable lessons, whether about the importance of international law, which arose largely in response to the excesses of the Thirty Years’ War (and yes, even today there are those who brazenly claim that international law is useless because it lacks violent enforcement), or about how progress in military affairs brings not only chemical and nuclear weapons, but also things like better logistics that lessen the suffering of the civilian population.

It also makes me think about the value of narratives. Is the narrative of tolerance valuable enough to justify a lie? And is the lie itself large enough to invalidate the narrative? After all, it is still better than the standard narrative of the Second World War (“the good guys crush the bad guys”) to say nothing of the nationalistic narratives of the nineteenth century, which never shied away from lies, fabrication of legends and outright falsifications.

> It was a bloody chaos. The troops plundered the civilian population, friend and foe alike.

Unfortunately, I think it was basically "business as usual" for the pre-industrial, pre-railroads warfare. See below.

> progress in military affairs brings not only chemical and nuclear weapons, but also things like better logistics that lessen the suffering of the civilian population

I think you've got that backwards, at least the part about logistics...

At any rate, I highly recommend the series on pre-industrial military campaign logistics by Bret Devereaux, starting with

https://acoup.blog/2022/07/15/collections-logistics-how-did-they-do-it-part-i-the-problem/

There, Devereaux explains how economic and technological affairs in the pre-industrial societies shaped military logistics, which determined the nature of the warfare. And how that looked from both military and civilian points of view.

Your concluding paragraph has me wondering, are there more pieces to come that will address the other narratives mentioned there (World War II, 19th century nationalism)? It would be nice if you were to write on those for completeness, if not for anything.