EU explained in 10 minutes

If you want to understand a country, you should pick a similar country that you are already familiar with, research the differences between the two and there you go, you are now an expert.

But this approach doesn’t quite work for the European Union. You might start, for instance, by comparing it to the United States, assuming that EU member countries are roughly equivalent to U.S. states. But that analogy quickly breaks down. The deeper you dig, the more confused you become.

You try with other federal states. Germany. Switzerland. But it doesn’t work either.

Finally, you try with the United Nations. After all, the EU is an international organization, just like the UN. But again, the analogy does not work. The facts about the EU just don’t fit into your UN-shaped mental model.

Not getting anywhere, you decide to bite the bullet and learn about the EU the hard way. You open the Wikipedia page. You sigh when you see the amount of text and notice all the unfamiliar names and acronyms. Yet, you start reading…

Apparently, the Council of Europe and the European Council are two entirely different things. And the Council of Europe isn’t even an EU institution, despite sharing the same flag. And notice that we are not even speaking of the Council of the European Union! And the European Parliament, despite its name, is not a legislature…

You browse around, you read articles, make notes, cross-reference stuff. But at a certain point you realize that you can’t bear the prospect of reading yet another dull and confusing wall of text.

At which point you grudgingly turn to this humble blog post.

***

To be clear: We are not going to dive deep into the EU’s institutions. You’ve already done that yourself, and it didn’t help. Instead, we are going to build a kind of conceptual skeleton, an intellectual scaffolding that can be used to put all those odd facts about the Union into perspective. Don’t expect many object-level details, but if I do my job well, you are going to see where your confusion stems from.

***

Consider a stereotypical Balkan house. How does it work? Obviously, the kitchen is for cooking and the bedrooms are for sleeping. That much is clear. But what about the rebar sticking out of the roof? What purpose could it possibly serve?

If you think of the house only as a place to live, you’ll have a hard time explaining it. Rebar seems nonsensical, even dangerous to the residents.

It’s only when you start treating the house as a dynamic structure, from its historical and evolutionary perspective so to say, that things begin to make sense. Of course, the rebar is there to anchor the next floor — if and when it’s ever built!

And suddenly, all the other odd details start to make sense, from the portable concrete mixer in the backyard to the faint imprints of scaffolding in the basement.

***

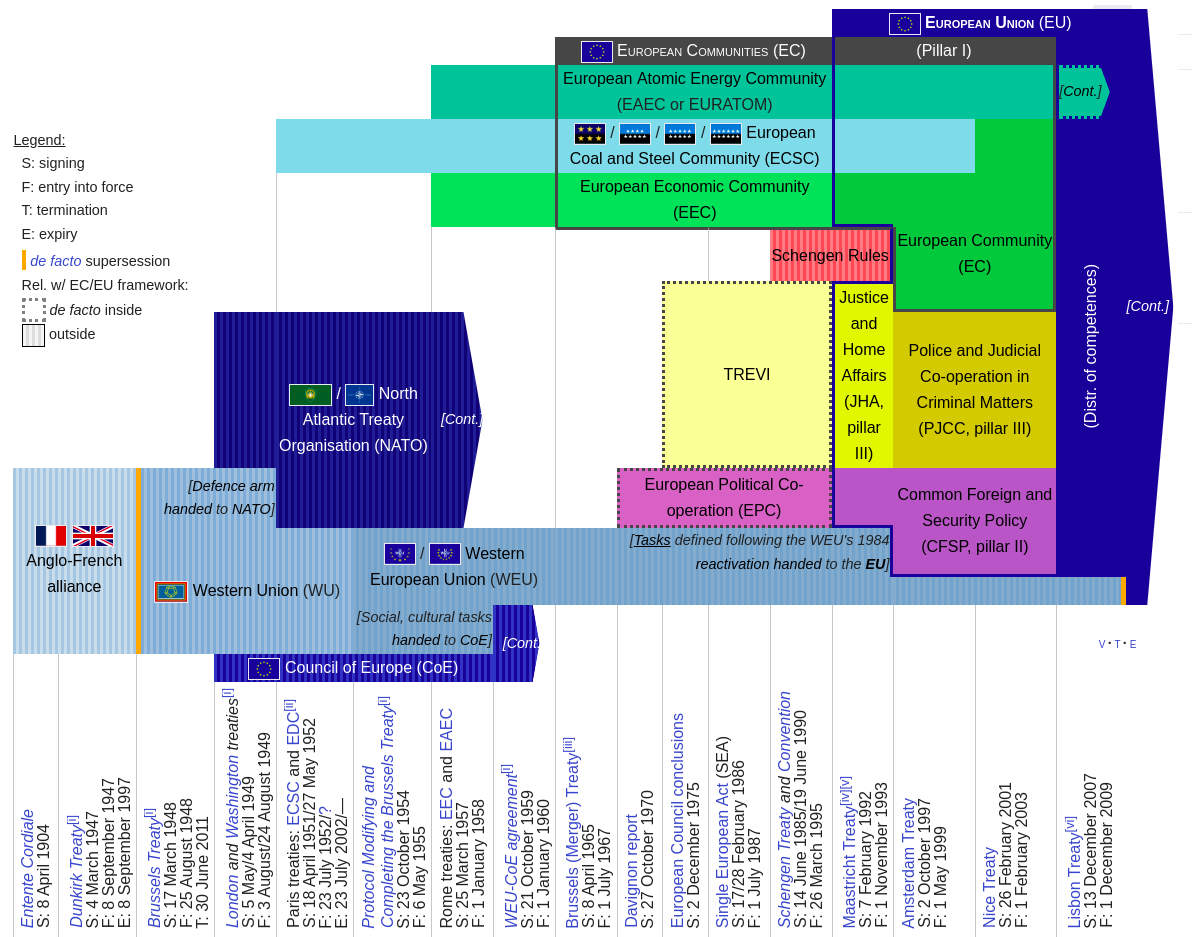

Consider the European Parliament. As already mentioned, it is not a true legislature. It can’t propose laws on its own. At first glance, that doesn’t make much sense. But take a look at the timeline!

1952 – Created as the Common Assembly. It’s completely toothless. Its task is to debate the decisions of the executive. Its members aren’t even elected. They are delegated by national parliaments.

1958 – Renamed to the European Parliamentary Assembly. It can now at least consult the legislation proposed by the executive.

1968 – Quietly renamed to the European Parliament, though this name isn’t yet formally recognized in the treaties.

1975 – Gains the power to reject the EU budget as a whole.

1979 – First direct elections.

1986 – The term European Parliament appears in the treaties for the first time. The Parliament can now propose amendments to the legislation.

1992 – Gains the power to approve (but not nominate!) the head of the executive.

1997 – Can veto legislation and approves the entire executive.

1999 – Flexes its muscle for the first time. Brings down the Santer Commission.

2009 – EU budget is prepared jointly by the Parliament and the Council.

See? The name “parliament” isn’t descriptive. It is not supposed to mean that the body in question is an actual parliament. It’s a statement of intent. And all the apparent weirdness stems from the fact that we are looking at an institution in the process of transformation. The odd stuff doesn’t necessarily have a practical, functional purpose. It’s historical. It’s evolutionary. It’s rebar sticking out of the roof.

***

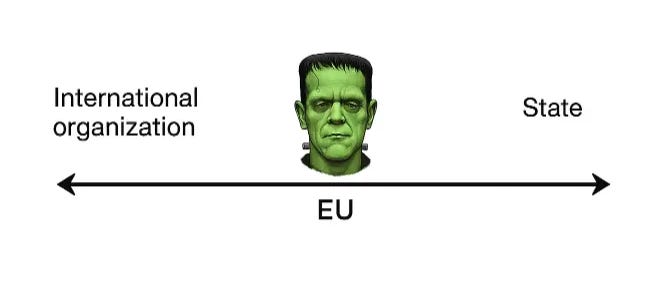

That begs a question: if the EU is transforming, what is it transforming from — and into what?

To answer the question, I have drawn a helpful diagram:

When it was created, the European Coal and Steel Community, the predecessor to the European Union, was an international organization. Established by international treaty, it was supposed to integrate the founding six’s coal and steel industries into a single common market. The idea was that by giving all members equal access to coal and steel — the key resources for waging war at the time — none of them (Germany, wink wink!) would be able to out-arm the others.

But it had already a tiny seed of a state built into it. It was deliberately designed so that the member states had to give up a little piece of their sovereignty to join in. The Community held binding powers over coal and steel production, pricing, and competition policy and the national governments could not veto its decisions individually. That was widely understood at the time. Britain, for example, was invited to join the club but declined, explicitly stating that it could not accept such a loss of sovereignty.

But that sovereignty loss was small, limited to the coal and steel industries. Again, this was deliberate. The founders have understood that creating a fully fledged federal Europe, as some had proposed, wasn’t politically viable. Instead, they adopted Jean Monnet’s method of “little steps”, that is, moving towards common, integrated political entity in gradual, iterated manner. The evolution of the European Parliament, with its tiny, almost trivial steps, fist renaming the Common Assembly to European Parliamentary Assembly, then to European Parliament, is a perfect illustration of that approach.

And that’s what the often heard phrase “ever closer union” actually means.

***

Since the EU’s inception in the 1950s, the Frankenstein, it seems, was always moving towards a unified state. But why is that? It’s a standard political process after all and there’s no reason it couldn’t run in reverse, moving back towards the international organization.

What follows is a speculation, but I’m including it nonetheless as it offers an example of how to even start thinking about the matter.

It seems to me that the process works like a ratchet. The pro-EU forces are mostly bureaucrats and policy-makers, for whom small, incremental changes are their daily bread and butter. The eurosceptics, on the other hand, tend to be people of big ideas, or often, of one big idea: national sovereignty. For them, small steps like trying to rename the European Parliament back to the European Parliamentary Assembly, or blocking it from participating in the drafting of the EU budget, are beneath their dignity.

Case in point: the Brexit negotiations. British government came to the table with the grand idea of reclaiming national sovereignty, but little else. It wasn’t even unified on such a basic question as whether to remain in or leave the common market. The EU side, by contrast, arrived with technical dossiers, raising poignant questions about how sausages would be traded between the UK and Northern Ireland.

So, for now at least, the dynamics appear to be asymmetric. Movement toward closer union is gradual, evolutionary and seemingly unstoppable. Movement in the opposite direction tends to happen suddenly, unpredictably and in leaps, like revolutions do.

***

All of that is fine, but it’s just the big picture. A historical one. It doesn’t offer much guidance on what to pay attention to on a daily basis.

An American columnist might write a commentary on the latest squabble between the Democrats and the Republicans. But what would his European counterpart do? Can you imagine a similar piece about disagreements between the EPP and ALDE? And have you, by the way, even heard those acronyms?

Yes, they are European political parties, but hardly anyone has heard of them. That’s because European parties are merely groupings of national parties, and they only really matter within the European Parliament, which itself is not a particularly powerful institution. The EU executive, on the other hand, where most of the real power lies, is apolitical, and the individual commissioners are appointed by member states, not by political parties.

Therefore, the real meat of political action isn’t in party politics. It lies elsewhere. If you want to follow what’s happening in Europe, you should focus on the relationship between the Union and the member states. Where an American pundit might write an article titled “What should the Democrats do about X?”, his European counterpart would instead ask, “What should Italy do about the matter?”

The kind of thing you should pay attention to is when, for example, Slovakia changes its constitution to grant national law precedence over EU law in “cultural and ethical matters.” That’s somewhat more limited than what Poland did back in 2021 but still, it’s a direct challenge to the Union. Will the EU respond by freezing funds, as it did with Poland, when it put more than 35 billion euros in COVID-19 recovery grants and loans on hold because of “rule-of-law violations”?

A different example: Viktor Orbán is clearly a security vulnerability for Europe, with Hungary repeatedly threatening to veto the aid to Ukraine. The underlying problem is that in certain areas — foreign policy in this case — decisions must be made unanimously. (Remember: veto equals unanimity equals national sovereignty.) This gives any national leader the power to block progress on any issue and to blackmail both the EU and other member states. And that’s without even considering the fact that, for Putin, all it takes to paralyze the entire Union is to bribe, threaten, or kompromat a single national leader.

In similar vein, Bulgaria was clearly pursuing a domestic political agenda in 2022 when it blocked North Macedonia’s candidacy to the EU based on accusations that the Macedonian language was simply Bulgarian by another name and Skopje was disrespecting its shared cultural and historic ties to Bulgarians. And again, the problem lies in the requirement for unanimity in the accession process.

To give a final example, the Russian threat, combined with the weakening of NATO, has created a clear demand for a common European army. Yet transferring the monopoly on violence from the member states to the Union would drastically alter the balance of power and therefore is a political nonstarter. That kind of dynamics is why you so often see proposals for “coalitions of the willing” — essentially subsets of countries ready to make unanimous decisions on specific matters. (Think of the Eurozone or the Schengen.)

***

On the more technical level, the decision-making procedures and incentives are heavily skewed in favor of the member states.

First, the strategic and political agenda of the EU is set by the European Council, that is, by the heads of national governments.

Second, the Council nominates the head of the executive, and while doing so, ensures that the President is sufficiently submissive and incapable of decisive action which could challenge the primacy of the member states. The individual commissioners, in turn, are nominated by the member states.

Third, in elections to the European Parliament, voters can only choose among their national parties and national candidates. A Spaniard cannot vote for a Finnish MEP, and a Finn cannot vote for a Spanish party. The Parliament has repeatedly approved proposals for trans-national voting lists, but the Council, not that anyone is surprised, disagrees.

Fourth, not only does the Union lack a common army or police force, it also has almost no alternative mechanisms to enforce its decisions. Given that state of affairs, it sometimes resorts to the crude tactic of blocking the in principle unrelated funds. European Public Prosecutor’s Office may be an early example of building an enforcement institution, but again, it’s a “coalition of the willing,” with Denmark, Ireland, and Hungary still outside of the club.

On the other hand, this systemic bias towards the member states is counterbalanced by how the political dynamics often play out. In times of crisis, the bargains struck among member states can sometimes lead to deeper integration.

When Germany was about to unify, for instance, France agreed to it only on the condition that Germany would support the creation of the monetary union — which later lead into adoption of a common currency.

Another example: when COVID hit, the EU was, for the first time, allowed to issue common debt.

Also, when an unpopular but necessary measure needs to be taken, national leaders are often quite happy to hand the decision over to the Union. This allows to avoid domestic backlash by shifting the blame to the EU and then melodramatically expressing moral outrage.

***

When it comes to nation states, everyone immediately knows what it means and what to expect. The concept was established long ago, in 1848, or even earlier. There’s no need to explain.

The European Union, on the other hand, is an experiment. It’s one of a kind. Nobody has a clear idea of what to expect. You see people using different, and not always mutually compatible, narratives. Some speak of the Union as a peace project. Some treat it as an exercise in economic cooperation. Others still view it as a path toward political unification. And some, of course, as a managerial conspiracy to overthrow the democratic system.

The fact that there’s no common knowledge of what the EU is supposed to be means that it lacks the basic stability of nation states, where everyone is more or less on the same page about what the state is for, even if they disagree on ideology or specific policies.

On the other hand, in an era when democratic institutions no longer generate the political legitimacy they once did, this instability gives the Union more wiggle room and the opportunity to try alternative approaches. It might accidentally stumble upon a model that better fits the modern landscape and come out on top. Or it might continue along its current trajectory and turn into a classic, fully fledged nation state just at the moment when that model ceases to work.

That Balkan house comparison is too spot on (and hilarious)

"A Spaniard cannot vote for a Finnish MEP, and a Finn cannot vote for a Spanish party."

It is not a vote by citizenship but residence of EU citizens. A Spanish national living in Finnland elects the Finnish candidates. A Finnish citizen in Spain will elect the Spanish candidate.

A technical special aspect is that MEP seats are not proportionate to population. Germany is 96 MEPs for 84 Million, Greece is 22 MEPS for 11 Mio residents, Malta is...

So European lists with one citizen-one vote make sense.