EU and Monopoly on Violence

The shape of Europe’s future political system is being decided right now.

Ben Landau-Taylor’s article in UnHerd makes a simple argument: simple, easy-to-use military technologies beget democracies. Complex ones concentrate military power in the hands of state militaries and favor aristocracies or bureaucracies.

One of the examples he gives is how “the rise of the European Union has disempowered elected legislatures de jure as well as de facto.”

Now, that’s just plain wrong. EU has no military and no police force (except maybe Frontex, but even that is far from clear-cut). The monopoly on violence remains firmly in the hands of the member states. Even coordination at the European level is not handled at the European level, but outsourced to NATO.

That said, Ben’s broader point is correct: groups capable of exerting violence will, in the long run, tend to get political representation. The groups that can’t will be pushed aside and their concerns ignored.

It may not happen at once. We are shielded from the brutal nature of the political system by layers of civilization, but in times of political uncertainty, when the veneer of civilization wears thin, the question of who is capable of violence does genuinely matter.

But it’s subtle. What exactly does ‘ability to exert violence’ mean?

A naive interpretation would be that whoever owns a gun holds political power. In a country where the entire population is armed, ‘the people’ can exert violence and therefore ‘the people’ are in power—ergo, democracy. Just look at Afghanistan!

No, it’s more complex than that. Individual violence matters little. If everyone is armed, the result is more often chaos or civil war than democracy. Power lies not with those who merely own guns, but with those who control the structures of organized violence, that is, armies, police forces, unions or criminal gangs.

Consider Myanmar. The military is largely separated from the rest of society. It has its own schools and hospitals, housing and welfare system. It controls large parts of the economy. Military families often live in closed compounds. Recruitment is heavily skewed toward the children of officers and NCOs, making it resemble a hereditary caste.

The result is what you would expect. The military holds political power a hardly anyone else does. And, by coincidence, the military is at present at war with virtually everyone else.

At the other end of the spectrum, consider XIX. century Prussia. At the beginning of the century, the military has become a popular institution. The Landwehr, based on universal conscription, replaced the earlier model of a professional armed force commanded by aristocrats.

The reason for this change, by the way, had little to do with the ‘people’ asserting political power. It stemmed instead from Napoleon’s restrictions on the size of the Prussian army. To circumvent these quotas, Prussia sought to build a large force by rapidly rotating conscripts through training.

But the outcome was inevitable: the aristocracy lost its monopoly on violence. The officer corps of the Landwehr was largely bourgeois, representing the middle class. This became evident during the revolution of 1848, when the Landwehr often sided with the progressives. Although the revolution ultimately failed, it prevented a full-scale return to the old order. The Landwehr remained a constant thorn in the side of the conservatives, and the progressives ensured it would not be replaced by a professional army.

In the following decades, we observe Bismarck locked in constant conflict with parliament over the question of a professional army. He ultimately achieved his goal, but not by dissolving the Landwehr — that was politically impossible at the time — but by sidelining it and making it basically a veterans’ club rather then an actual fighting force.

In Switzerland, the militia system established after 1848 has, unlike in Germany, survived to the present day. A Swiss saying goes, ‘We don’t have an army. We are an army.’ While often mocked by the left, there is a fundamental truth to it: it is difficult to deploy an army against the people when the army is the people.

But not so fast! In 1918, workers called a general strike, and the government deployed troops against them. In the end, the workers backed down. But how was that even possible? Doesn’t a people’s army mean that such a thing can’t be done?

And as always, the details matter. The workers were, due to universal conscription, part of the army, but the officers are overwhelmingly from the middle class. Ordinary soldiers may have felt sympathy for the workers, but their commanders certainly did not. Moreover, the government made sure to deploy the troops from the rural regions, where there was little industry, where the soldiers were mostly farmers, leaned conservative and had little sympathy for the workers.

We see these dynamics repeated again and again, even in modern times. Who owns guns matters, but so do the details of military structure, the composition of the troops, and their loyalty to their leaders.

During the Rose Revolution in Georgia in 2003, President Shevardnadze attempted to deploy the army against the protesters. But despite his position as commander-in-chief, the army ignored his orders. Shevardnadze fell, and the revolution succeeded.

In Turkey, the military once functioned as a caste of its own, much like in Myanmar, regularly toppling elected leaders. But in 2016, the coup against Erdoğan failed: soldiers refused to use violence against protesters, and Erdoğan remains in power to this day, the power of the military diminished.

The point is that the way violence is institutionalized matters a lot. The nature of a political system is often downstream from seemingly minor details, how the officer corps is selected, how troop loyalty is ensured or how the command structure works overall.

Which brings us back to the EU.

At the moment it has no access to organized violence, but the times are changing. The Russian threat in the east combined with a weakening of NATO makes a lot of people have second thoughts.

At the national level, the change is already underway.

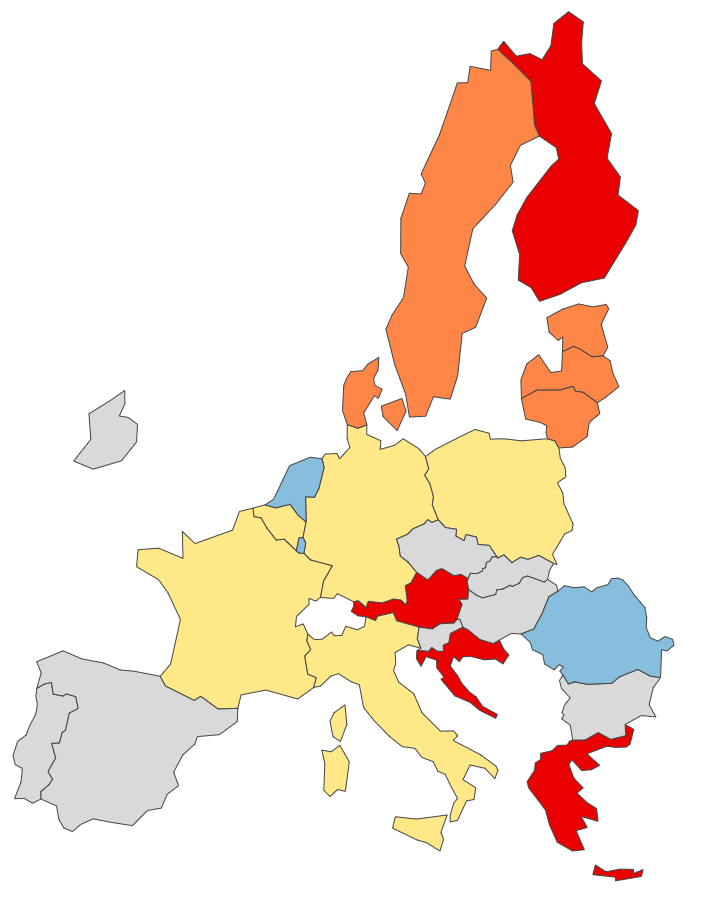

Sweden was early to the party, reintroducing compulsory military service in 2017. Conscription is already in force in the countries along the bloc’s eastern flank, be it Finland or the Baltic countries.

Some countries are experimenting with voluntary service. The Netherlands already has such a system, while, Belgium and Romania are considering it.

The Greece has entirely different concerns. NATO’s famous Article 5 covers external attacks, not conflicts between member states, meaning there is no NATO umbrella shielding Greece from Turkey. Hence, conscription.

But whatever the changes at the national level, in the end of the day, small Estonia could never stand up to Russia on its own. The EU as a whole, however, absolutely could. Despite its vast territory, Russia’s economy is smaller than Italy’s and if the EU had a unified army, Russia wouldn’t stand a chance.

But with many splintered national armies you get outcomes like this one:

The French army painfully realized how difficult it was to cross Europe in the spring of 2022, when it deployed a battalion to Romania in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. “We discovered the extent of the administrative red tape. There’s a war in Ukraine, but customs officials explain that you don’t have the right tonnage per axle and that your tanks aren’t allowed to cross Germany.”

The solution seems obvious: create a unified European army.

But who would command it? Would the role of commander-in-chief go to Ursula von der Leyen? Whatever one thinks of her, she was not chosen by popular vote but through haggling among member states. True, she was selected by heads of state who, in most cases, were themselves chosen by national parliaments, which in turn were elected by the people. So yes, there is a measure of political accountability. But at this level of indirection, it is weak, if not imperceptible.

This democratic deficit in the EU (consider also that the Commission drafts legislation rather than the Parliament, concentrating the power in the hands of the executive) doesn’t matter much for now, because the classic system of checks and balances is effectively replaced by the member states’ complete control over the Union. Von der Leyen can do barely anything unless she has member states on board.

However, if the monopoly on violence were to fall into the hands of the Commission, this system would break down, and the democratic deficit would become downright dangerous. The Commission could compel member states, yet it would remain unchecked by voters. The picture has a certain junta-like feel to it and the fact that the supreme leader happens to have a ‘von’ in her name does not exactly help.

Structural changes to the organization of violence in Europe are in the air. And the exact shape of these changes, the details that almost nobody pays any attention to, the nature of conscription, the process of selection of the officer corps, how the army is subjugated to the elected officials, all of that is going to play decisive role in shaping the political system in Europe in the century to come.