Meditations on Doge

Lessons from shutting down institutions in Eastern Europe.

Imagine living in the former Soviet republic of Georgia in early 2000’s:

All marshrutka [mini taxi bus] drivers had to have a medical exam every day to make sure they were not drunk and did not have high blood pressure. If a driver did not display his health certificate, he risked losing his license. By the time Shevarnadze was in power there were hundreds, probably thousands , of marshrutkas ferrying people all over the capital city of Tbilisi. Shevernadze’s government was detail-oriented not only when it came to taxi drivers. It decided that all the stalls of petty street-side traders had to conform to a particular architectural design. Like marshrutka drivers, such traders had to renew their licenses twice a year. These regulations were only the tip of the iceberg. Gas stations, for example, had to be located at a specific distance from the street.

[…]

These regulations, and thousands like them, were never intended to be implemented. Nobody really expected marshrutka drivers to have a daily medical exam, and they didn’t. But by creating such a rule, the Georgian state immediately created a pretext for prosecuting the entire fleet of marshrutka drivers. To avoid this, the drivers had to pay bribes. So did the petty traders. So did the gas stations.

— Acemoglu & Robinson: The Narrow Corridor

One lesson, I guess, is that the tough approach, the ideology of "law and order," the belief that more numerous and stricter laws lead to a stronger rule of law, does not necessarily work. In fact, the opposite can be true. Laws that are too strict can make it impossible for citizens to comply, and so, willy-nilly, they end up bribing police officers and bureaucrats.

The professions of police officer or judge become attractive, even if the salaries are low. In Georgia, the position of a police officer was being sold, and new law enforcement officers were expected to provide their own uniforms and weapons at their own expense. Police officers couldn’t stop taking bribes because they simply couldn’t survive on their official salaries. Conversely, the flow of money from bribes through the state administration created a strong incentive to introduce even more strict laws, which in turn generated even greater bribes.

But that’s not the main point I wanted to make. What I’m really trying to emphasize is that the Georgian state in the 1990s and early 2000s was extremely ineffective at delivering services to its citizens, whether justice, defense, electricity, or basic everyday security. The situation was dire, even by the already low standards of Russia at the time. Here’s what Andrey Illarionov, a former advisor to Putin, had to say:

There’s no comparing it to Russia. [...] It was truly a country in a state of collapse. An economic, political, social, legal collapse. A country where power was wielded by bandits in the literal sense of the word. A common occurrence was that when, for example, some more or less successful businessmen arrived in Tbilisi, they’ve sent armed men to accompany him so that he could travel those 15 minutes between the airport and the city without being kidnapped and held for ransom. And when some kind of godfather or mafia boss arrived, they were welcomed by the Minister of the Interior.

Unsurprisingly, between 1991 and 1994, the Georgian economy contracted by 77%. The country's largest export was scrap metal.

Then, in 2003, the Rose Revolution took place, the first of the so-called "color revolutions", and Mikhail Saakashvili became president with an overwhelming 96.2% mandate to reform the country.

Saakashvili is a colorful character: former Georgian prime minister, leader of the Rose Revolution, and president during the brief war with Russia. After his presidency, he obtained Ukrainian citizenship and became the governor of the Odesa Oblast. He later accused Ukrainian President Poroshenko of corruption, was stripped of his citizenship, and became stateless. At one point, he was arrested on a rooftop in Kyiv while his supporters began building barricades. Eventually, under President Zelensky, he regained his Ukrainian citizenship. He later returned to Georgia, got arrested and now he’s reportedly dying in a prison hospital, possibly at Putin’s behest.

That being said, his minister of economy, the spiritual father of the Georgian reforms, a former Soviet biologist and Russian businessman Kakha Bendukidze is no less interesting.

Generally speaking, libertarians do not occur in the wild in Europe. However, there exists a rare and peculiar breed: the Eastern European libertarian. His distrust of government does not arise from deep philosophical conviction or even a particular love of liberty. It comes from firsthand experience with the (post-)communist state.

"Someone complimented me on quoting Hayek,” Bendukidze recalls, “and I replied that I hadn't quoted anyone. I had never read Hayek. I was quoting myself."

Bendukidze began his business career in the Soviet Union, earning his first million during the Gorbachev era. He later became the CEO of Uralmash, a heavy machinery manufacturing company based in Yekaterinburg.

“When you own a vodka business,” Bendukidze says, “protection racketeers will come and take the vodka. With heavy machinery, it gets more difficult.”

But what protection racketeers can’t do, the state can. When Putin came to power, the purge of the disloyal oligarchs began. Oligarch Boris Berezovsky, then already in exile, remarked: "Bendukidze was not among Putin's friends and understood sooner than others that everything would eventually be taken away from him... Bendukidze had far from exhausted his potential, but at that moment the Russian authorities did not need such talented people."

Bendukidze sold his shares in Uralmash and moved to his native Georgia. And soon enough he joined Saakashvili in his attempt to reform the Georgian state.

They did a host of reforms, rising the economic growth to 7% yearly and Georgia, that was still in 100th place in the Ease of Doing Business index in 2006, soared up sharply and by the end of Saakashvili's reign it was already in eighth place, among the most developed countries.

But that’s a story for another day. For the purposes of this article, the most interesting reform is the reform of the police:

The most visible, tangible, and celebrated reform was the abolishment of the Soviet-style road police, the GAI (State Automobile Inspection). Georgia’s road police had nothing to do with law enforcement and created no public good; its sole purpose was to extract bribes. To deal with the problem, in 2005 we fired all of the traffic police in Georgia, cutting 30,000 police from the payroll overnight. Following this extraordinary step, Georgia had no traffic police for some time. The fact that traffic did not become less orderly or unsafe was evidence that the system had been designed not for safety but rather to extort bribes from motorists.

(By the way, the quote comes from The Great Rebirth: Lessons from the Victory of Capitalism over Communism. If you want to know more about post-communist reforms in the Eastern Europe, straight from the horse’s mouth, that is, from the very people who implemented the reforms, then that’s the book for you.)

Very few of the dismissed traffic police were taken back into the service. Salaries of the new officers were raised by a factor of 15–40. It was essential for the new police to gain the trust and confidence of citizens. To ensure that they do so, every year they go through training and selection, after which the least efficient are dismissed and new officers hired.

To boost the public image of the police, new, transparent, headquarters were built. People in discos danced to the new police anthem.

Soon after the mass firing of the Gaishniks, Georgia had a new and modernized police institution. The share of the Georgian people that had confidence in the police rose from 5 percent in 2004 to an astonishing 87 percent in 2012, and Tbilisi became one of the safest cities in Europe.

Tyler Cowen interviews Jennifer Pahlka, founder of Code for America and co-founder of the United States Digital Service (check her substack), a person who has tried to reform the US civil service from inside, and asks:

[Do] we need something like DOGE? I’ve lived near DC for about 40 years of my life. I haven’t seen anyone succeed with regulatory reforms. You can abolish an agency, but to really reform the process hasn’t worked. Maybe the best iteration we can get is to break a bunch of things now. That will be painful, people will hate it, but you have a chance in the next administration to put some of them back together again.

Pahlka sympathizes, but regrets that the disruption did not happen in a more orderly way. Cowen suggests it could have been done gradually:

Just take government agencies and sidestep them. Create a new NIH, call it something else. […] In the meantime, we cut the budget of the current NIH, say, in half. […] Why not just keep on doing that? Create new things and destroy parts of old ones.

Pahlka is skeptical:

That does happen. That’s what we call the bureaucratic rigidity cycle. We haven’t, I think, been disciplined enough about dismantling the old when we create the new. I experienced that myself helping start USDS, the United States Digital Service.

It’s creating something new, but it still […] just had far less power than the existing infrastructures, CIOs of agencies, the procurement frameworks. That stuff has a life of its own and a power of its own. If you are creating these skunk works to disrupt the old stuff, it has to actually disrupt the old stuff. You can’t just add.

Compare that with what Mart Laar, the former prime minister of Estonia from the time of the post-soviet reforms, has to say:

Our insight was simple: It is not possible to teach an old dog new tricks. Old communist apparatchiki had based their entire careers on lies and deceit. It was unrealistic to expect them to change. The state apparatus inherited from the Soviet Union was unsuitable for implementing appropriate policies. Its preferred mode of command was phone calls from superiors; written law meant little and ethics nothing. Therefore, it was important to do away with the old attitudes and relations, as radically as possible. The ties with the Soviet past had to be cut for good. The more radical the change and the more people and politicians of the previous generation are replaced in the governing bodies, the more credible the reform and the greater the chances of success. My party won the election campaign in 1992 with the slogan “Clear the place!”

And of course, this is the same as Bendukidze’s “destructive destruction,“ a wordplay on Schumpeter’s concept of “creative destruction”.

The crux of the discussion is whether reforms should be done gradually, or in one sweeping go.

Here’s Estonia’s Mart Laar again:

With regard to the question of whether transition economies should opt for a “gradual” approach or “shock therapy,” countries that have attempted to carry out reforms slowly in stages have faced serious difficulties. The social price of the reforms has been as high as or even higher than in countries in which decisive action was taken, and at some point it has nevertheless been necessary to adopt policies containing elements of shock therapy.

Gradual reforms faced two major challenges:

First, when the consequences of the reforms began to affect people and the standard of living declined, an electoral backlash was almost inevitable. If the reforms were slow, they would remained unfinished by the time the new government was elected, which would likely stall or even revers them.

Second, the communist apparatchiks had their own agency. If reforms dragged on, they would have time to regroup, ally with organized crime, and recapture the institutions.

This is exactly what happened in Bulgaria, where the communists won the first election after the revolution:

In addition to the Communist Party retaining its power, the meandering path to reforms created a second feature of transition in Bulgaria: The former secret police, the best-organized institution under socialism, took control of parts of the economy, in particular the banking sector and the exporting business.

[…]

The takeover of the major exporting companies by members of the former secret police created a third feature of Bulgaria’s transition: the emergence of organized crime and its preeminence throughout the transition period. Members of organized crime started bloody gang wars over the contraband channels for selling drugs and weapons abroad, as well as for dominance over the energy sector. That dominance required the cooperation of the police and customs officials, which they secured through bribes or threats.

The struggle for dominance went all the way up to the former communist leadership and the leadership of the secret service. In one fight over lucrative Russian energy contracts, in October 1996, the last communist prime minister, Andrei Lukanov, was assassinated. […] Between 1996 and 2008, some 300 members of the Bulgarian mafia, including some political figures, were assassinated by rival factions.

At the time, it wasn’t clear whether gradual or abrupt reform was the better approach. Even reasonable experts like Joseph Stiglitz advocated for a slow transition, fearing an anti-democratic backlash.

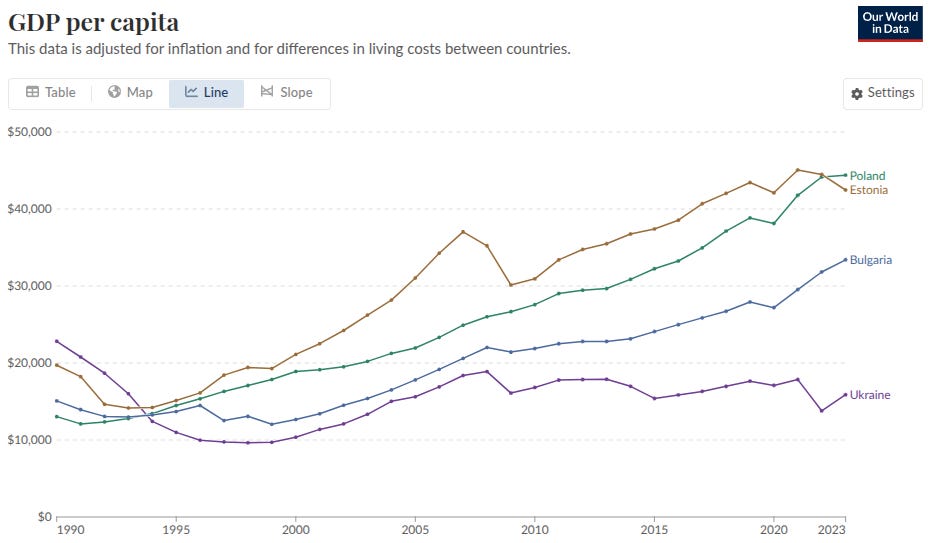

Only in hindsight do we now know that countries opting for shock therapy, such as Poland and Estonia, ended up much better off than those that chose a gradual approach, like Bulgaria and Ukraine:

Anyway, back to the original topic, there are strong reasons to doubt that the lessons from the rapid and harsh reforms in Eastern Europe are applicable to the US, or indeed to any other developed country or organization such as the EU.

First, the institutions in post-communist countries were already dysfunctional, and in some cases, provided little to no value. Therefore, dismantling them was not particularly painful.

Here’s Saakashvili’s argument for closing down government agencies:

Let's say we abolished the sanitary inspection. Nobody goes and checks if there are cockroaches in the restaurant kitchen... But will there be fewer cockroaches in the kitchen just because the sanitary inspection exists? We all know that the sanitary inspection goes there only to take bribes. And the owner, instead of spending money on improving the restaurant, on cleaning the kitchen — including from cockroaches — spends it on other cockroaches from the sanitary inspection. [The same applies to the fire inspection.] It would be good, of course, if we were such a disciplined supernation that the fire inspection would actually check fire safety. [But we are not.]

However, if an institution like sanitary inspection is functioning properly, shutting it down will cause real harm, leading to more infections and food poisonings. Abolishing fire inspection would result in more fires. This argument is even stronger for vital services such as healthcare, social security, or tax collection.

Second, the reformers in Eastern Europe were not acting blindly. They had a clear goal, an endpoint they wanted to reach: Namely, a state that would function much like the existing Western democracies.

Not so today. The civil service in western countries clearly struggles to keep up with the ever more complex and dynamic world. (If you want to understand the nitty-gritty details of that struggle read the excellent Pahlka’s book on the topic.) It clearly needs a reform, but nobody knows what kind of reform would work. Unlike in post-Soviet states in 1990’s, there’s no one to copy, no one to get guidance from. We are in experimentation mode.

So, short of disbanding institutions wholesale without a clear plan, merely hoping they’ll improve when rebuilt, what else can be done?

> Only in hindsight do we now know that countries opting for shock therapy, such as Poland and Estonia, ended up much better off than those that chose a gradual approach, like Bulgaria and Ukraine:

But Russia also famously opted for shock therapy, and did not manage to transition to a stable, capable and accountable rule-of-law democracy, to put it ridiculously mildly.

Perhaps a better explanation is that countries geographically and culturally closer to western/central Europe tended to be pulled into European norms and to see economic benefits, compared to those closer to the sphere of influence of the Russian kleptocracy.

> [when transitions were gradual], the communist apparatchiks had their own agency. If reforms dragged on, they would have time to regroup, ally with organized crime, and recapture the institutions.

Russia, 30 years after their a sharp transition is ruled by soviet-era secret police officer, allied with organized crime, who has absolutely captured the institutions.

> Anyway, back to the original topic, there are strong reasons to doubt that the lessons from the rapid and harsh reforms in Eastern Europe are applicable to the US, or indeed to any other developed country or organization such as the EU.

Well, I can at least agree it's not a good idea in developed countries. Institutions are hard to build, hard to reform, easy to destroy, and when degraded leave great opportunities for corruption.