Life at the Frontlines of Demographic Collapse

What the real degrowth looks like.

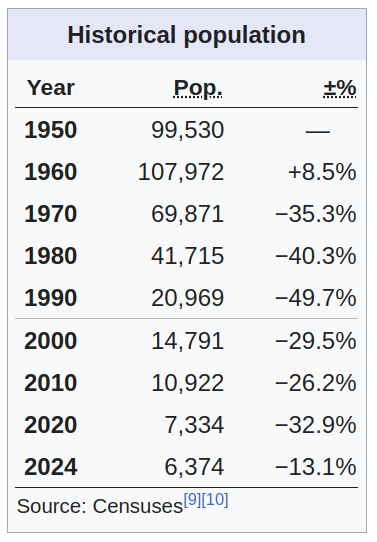

In 1960, Yubari, a former coal-mining city on Japan’s northern island of Hokkaido, had roughly 110,000 residents. Today, fewer than 7,000 remain. The share of those over 65 is 54%. The local train stopped running in 2019. Seven elementary schools and four junior high schools have been consolidated into just two buildings. Public swimming pools have closed. Parks are not maintained. Even the public toilets at the train station were shut down to save money.

Much has been written about the economic consequences of aging and shrinking populations. Fewer workers supporting more retirees will make pension systems buckle. Living standards will decline. Healthcare will get harder to provide. But that’s dry theory. A numbers game. It doesn’t tell you what life actually looks like at ground zero.

And it’s not all straightforward. Consider water pipes. Abandoned houses are photogenic. It’s the first image that comes to mind when you picture a shrinking city. But as the population declines, ever fewer people live in the same housing stock and water consumption declines. The water sits in oversized pipes. It stagnates and chlorine dissipates. Bacteria move in, creating health risks. You can tear down an abandoned house in a week. But you cannot easily downsize a city’s pipe network. The infrastructure is buried under streets and buildings. The cost of ripping it out and replacing it with smaller pipes would bankrupt a city that is already bleeding residents and tax revenue. As the population shrinks, problems like this become ubiquitous.

The common instinct is to fight decline with growth. Launch a tourism campaign. Build a theme park or a tech incubator. Offer subsidies and tax breaks to young families willing to move in. Subsidize childcare. Sell houses for €1, as some Italian towns do.

Well, Yubari tried this. After the coal mines closed, the city pivoted to tourism, opening a coal-themed amusement park, a fossil museum, and a ski resort. They organized a film festival. Celebrities came and left. None of it worked. By 2007 the city went bankrupt. The festival was canceled and the winners from years past never got their prize money.

Or, to get a different perspective, consider someone who moved to a shrinking Italian town, lured by a €1 house offer: They are about to retire. They want to live in the country. So they buy the house, go through all the paperwork. Then they renovate it. More paperwork. They don't speak Italian. That sucks. But finally everything works out. They move in. The house is nice. There's grapevine climbing the front wall. Out of the window they see the rolling hills of Sicily. In the evenings, they hears dogs barking in the distance. It looks exactly like the paradise they'd imagined. But then they start noticing their elderly neighbors getting sick and being taken away to hospital, never to return. They see them dying alone in their half-abandoned houses. And as the night closes in, they can't escape the thought: "When's my turn?" Maybe they shouldn't have come at all.

***

The instinctive approach, that vain attempt to grow and repopulate, is often counterproductive. It leads to building infrastructure, literal bridges to nowhere, waiting for people that will never come. Subsidies quietly fizzle out, leaving behind nothing but dilapidated billboards advertising the amazing attractions of the town, attractions that closed their gates a decade ago.

The alternative is not to fight the decline, but to manage it. To accept that the population is not coming back and ask a different question: how do you make a smaller city livable for those who remain? In Yubari, the current mayor has stopped talking about attracting new residents. The new goal is consolidation. Relocating the remaining population closer to the city center, where services can be still delivered, where the pipes are still the right size, where neighbors are close enough to check on each other.

Germany took a similar approach with its Stadtumbau Ost, a federal program launched after reunification to address the exodus from East to West, as young people moved west for work, leaving behind more than a million vacant apartments. It paid to demolish nearly 300,000 housing units. The idea was not to lure people back but to stabilize what was left: reduce the housing surplus, concentrate investment in viable neighborhoods, and stop the downward spiral of vacancy breeding more vacancy. It was not a happy solution, but it was a workable one.

Yet this approach is politically toxic. Try campaigning not on an optimistic message of turning the tide and making the future as bright as it once used to be, but rather by telling voters that their neighborhood is going to be abandoned, that the bus won’t run anymore and that all the investment is going to go to a different district. Try telling the few remaining inhabitants of a valley that you can’t justify spending money on their flood defenses.

Consider the España Vaciada movement representing the depopulating interior of Spain, which has achieved some electoral successes lately. It is propelled by real concerns: hospital patients traveling hours to reach a proper facility, highways that were never expanded, banks and post offices that closed and never reopened. But it does not champion managed decline. It champions the opposite: more investment, more infrastructure, more services. Its flagship proposal, the 100/30/30 plan, demands 100-megabit internet everywhere, no more than 30 minutes to basic services, no more than 30 kilometers to a major highway. They want to reopen what was closed. They want to see more investment in healthcare and education. They want young people back in the regions.

And it’s hard to blame them. But what that means on the ground, whether in Spain or elsewhere, is that the unrewarding task of managing the shrinkage falls to local bureaucrats, not to the elected politicians. There’s no glory in it, no mandate, just the dumpster fire and whatever makeshift tools happen to be at hand.

***

You can think of it as, in effect, a form of degrowth. GDP per capita almost always falls in depopulating areas, which seems counterintuitive if you subscribe to zero-sum thinking. Shouldn’t fewer people dividing the same economic pie mean more for each?

Well, no. It’s a negative-sum game. As the town shrinks, the productive workforce, disheartened by the lack of prospects, moves elsewhere, leaving the elderly and the unemployable behind. Agglomeration effects are replaced by de-agglomeration effects. Supply chains fragment. Local markets shrink. Successful firms move to greener pastures.

And then there are the small firms that simply shut down. In Japan, over half of small and medium-sized businesses report having no successor. 38% of owners above 60 don’t even try. They report planning to close the firm during their generation. But even if they do not, the owner turns seventy, then seventy-five. Worried clients want a guarantee of continued service and pressure him to devise a succession plan. He designates a successor — maybe a nephew or a son-in-law — but the young man keeps working an office job in Tokyo or Osaka. No transfer of knowledge happens. Finally, the owner gets seriously ill or dies. The successor is bewildered. He doesn’t know what to do. He doesn’t even know whether it’s worth it. In fact, he doesn’t really want to take over. Often, the firm just falls apart.

*** So what is being done about these problems?

Take the case of infrastructure and services degradation. The solution is obvious: manage the decline by concentrating the population.

In 2014, the Japanese government initiated Location Normalization Plans to designate areas for concentrating hospitals, government offices, and commerce in walkable downtown cores. Tax incentives and housing subsidies were offered to attract residents. By 2020, dozens of Tokyo-area municipalities had adopted these plans.

Cities like Toyama built light rail transit and tried to concentrate development along the line, offering housing subsidies within 500 meters of stations. The results are modest: between 2005 and 2013, the percentage of Toyama residents living in the city center increased from 28% to 32%. Meanwhile, the city’s overall population continued to decline, and suburban sprawl persisted beyond the plan’s reach.

What about the water pipes? In theory, they can be decommissioned and consolidated, when people move out of some neighborhoods. At places, they can possibly be replaced with smaller-diameter pipes. Engineers can even open hydrants periodically to keep water flowing. But the most efficient of these measures were probably easier to implement in the recently post-totalitarian East Germany, with its still-docile population accustomed to state directives, than in democratic Japan.

***

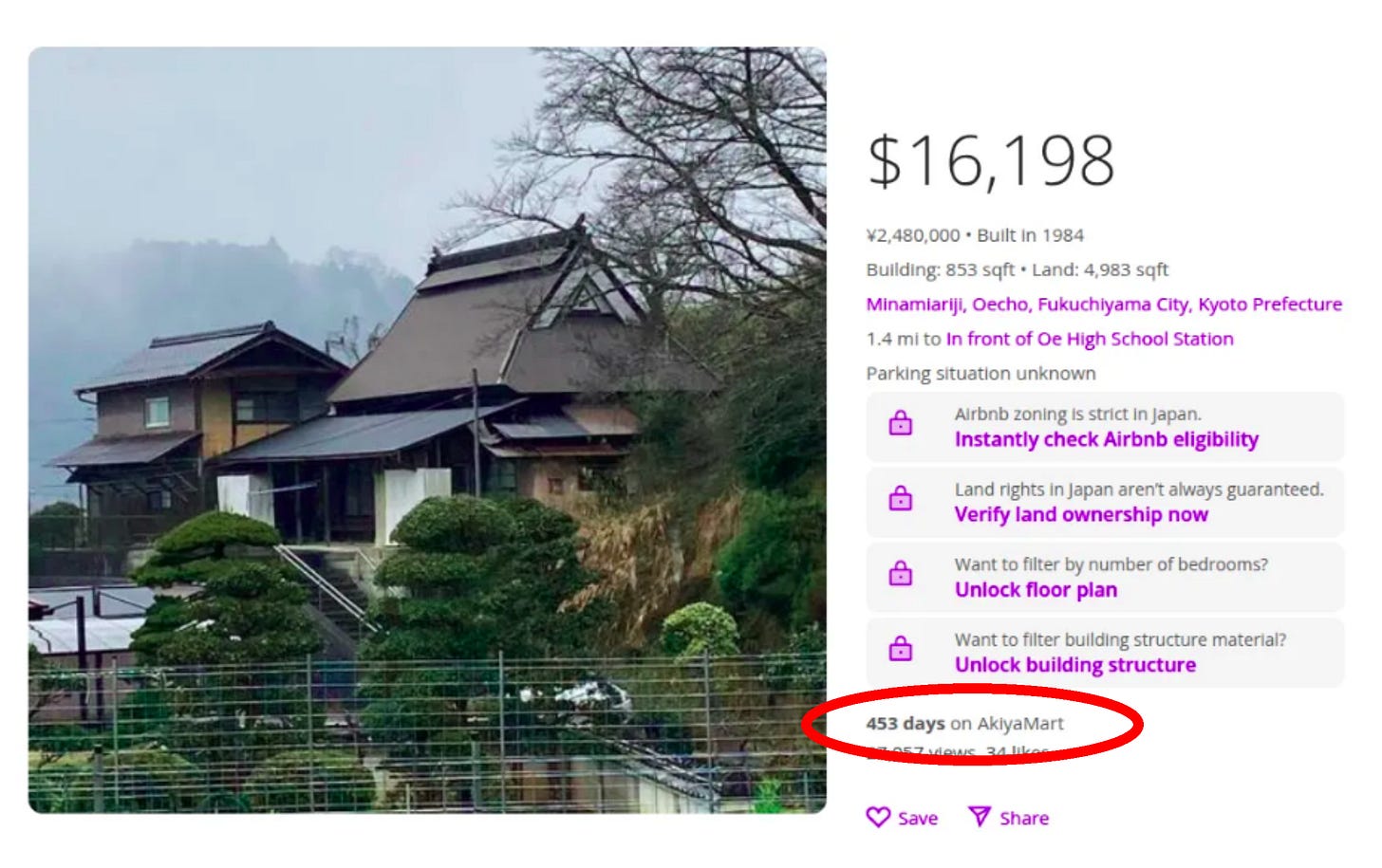

And then there’s the problem of abandoned houses.

The arithmetic is brutal: you inherit a rural house valued at ¥5 million on the cadastral registry and pay inheritance tax of 55%, only to discover that the actual market value is ¥0. Nobody wants property in a village hemorrhaging population. But wait! If the municipality formally designates it a “vacant house,” your property tax increases sixfold. Now you face half a million yen in fines for non-compliance, and administrative demolition costs that average ¥2 million. You are now over ¥5 million in debt for a property you never wanted and cannot sell.

It gets more bizarre: When you renounce the inheritance, it passes to the next tier of relatives. If children renounce, it goes to parents. If parents renounce, it goes to siblings. If siblings renounce, it goes to nieces and nephews. By renouncing a property, you create an unpleasant surprise for your relatives.

Finally, when every possible relative renounces, the family court appoints an administrator to manage the estate. Their task is to search for other potential heirs, such as "persons with special connection," i.e. those who cared for the deceased, worked closely with them and so on. Lucky them, the friends and colleagues!

Obviously, this gets tricky and that’s exactly the reason why a new system was introduced to allows a property to be passed to the state. But there are many limitations placed on the property — essentially, the state will only accept land that has some value.

In the end, it's a hot potato problem. The legal system was designed in the era when all property had value and implicitly assumed that people wanted it. Now that many properties have negative value, the framework misfires, creates misaligned incentives and recent fixes all too often make the problem worse. Tax penalties meant to force owners to renovate only add to the costs of the properties that are already financial liabilities, creating a downward price spiral.

Maybe the problem needs fundamental rethinking. Should there be a guaranteed right to abandon unwanted property? Maybe. But if so, who bears the liabilities such as demolishing the house before it collapses during an earthquake and blocks the evacuation routes?

***

Well, if everything is doom and gloom, at least nature benefits when people are removed from the equation, right?

Let’s take a look.

Japan has around 10 million hectares of plantation forests, many of them planted after WWII. These forests are now reaching the stage at which thinning is necessary. Yet because profitability has declined — expensive domestic timber was largely displaced by cheap imports long ago — and the forestry workforce was greatly reduced, thinning often does not occur. As a result, the forests grow too dense for light to penetrate. Little or nothing survives in the understory. And where something does manage to grow, overpopulated deer consume new saplings and other vegetation such as dwarf bamboo, which would otherwise help stabilize the soil. The result is soil erosion and the gradual deterioration of the forest.

The deer population, incidentally, is high because there are no wolves, the erstwhile apex predators, in Japan. But few people want them reintroduced. Instead, authorities have extended hunting seasons and increased culling quotas. In an aging and depopulating countryside, however, there are too few hunters to make use of these measures. And so, this being Japan, robot wolves are being deployed in their stead.

***

Finally, care for the elderly is clearly the elephant in the room. Ideas abound: Intergenerational sharehouses where students pay reduced rent in exchange for “being good neighbors.” Projects combining kindergartens with elderly housing. Denmark’s has more than 150 cohousing communities where residents share meals and social life. But the obvious challenge is scale. These work for dozens, maybe hundreds. Aging countries need solutions for millions.

And then again, there are robot nurses.

***

It’s all different kinds of problems, but all of them, in their essence, boil down to negative-sum games.

Speaking of those, one tends to think of it as of the pie shrinking. And there’s an obvious conclusion: if you want your children to be as well off as you are, you have to fight for someone else’s slice. In a shrinking world, one would expect ruthless predators running wild and civic order collapsing.

But what you really see is quite different. The effect is gradual and subtle. It does not feel like a violent collapse. It feels more like the world silently coming apart at the seams. There’s no single big problem that you would point to. It feels like if everything now just works a bit worse than it used to.

The bus route that ran hourly now runs only three times a day. The elementary school merged with the one in the next town, so children now commute 40 minutes each way. Processing paperwork at the municipal office takes longer now, because both clerks are past the retirement age. The post office closes on Wednesdays and Fridays and the library opens only on Tuesdays. The doctor at the neighborhood clinic stopped accepting new patients because he’s 68 and can’t find a replacement. Even the funeral home can’t guarantee same-day service anymore. Bodies now have to wait.

You look out of the window at the neighboring house, the windows empty and the yard overgrown with weeds, and think about the book club you used to attend. It stopped meeting when the woman who used to organize it moved away. You are told that the local volunteer fire brigade can’t find enough members and will likely cease to operate. You are also warned that there may be bacteria in the tap water. You are told to boil your water before drinking it.

Sometimes you notice how the friends and neighbors are getting less friendly each year. When you need a hand, you call them, but somehow today, they just really, really can’t. It’s tough. They’ll definitely help you next time. But often, they are too busy to even answer the phone. Everyone now has more people to care for. Everyone is stretched out and running thin on resources.

When you were fifty and children started to leave the home, you and your friends, you used to joke that now you would form an anarcho-syndicalist commune.

Ten years later you actually discuss a co-living arrangement, and all you can think about is the arithmetic of care: would you be the last one standing, taking care of everybody else?

Finally someone bites the bullet and proposes moving together but signing a non-nursing-care contract first. And you find yourself quietly nodding in approval.