Erasmus: Social Engineering at Scale

When Sofia Corradi died on October 17th, the press was full of obituaries for the spiritual mother of Erasmus, the European student exchange programme, or, in the words of Umberto Eco, “that thing where a Catalan boy goes to study in Belgium, meets a Flemish girl, falls in love with her, marries her, and starts a European family.”

Yet none of the obituaries I’ve seen stressed the most important and interesting aspect of the project: its unprecedented scale.

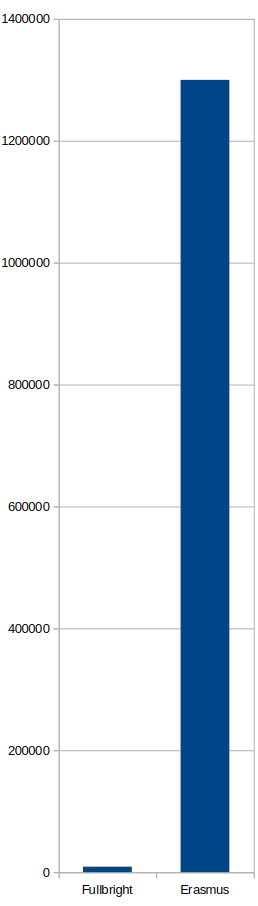

The second-largest comparable programme, the Fulbright in the United States, sends around nine thousand students abroad each year. Erasmus sends 1.3 million.

So far, approximately sixteen million people have taken part in the exchanges. That amounts to roughly 3% or the European population. And with the ever growing participation rates the ratio is going to get even gradually even higher.

Is short, this thing is HUGE.

***

As with many other international projects conceived in Europe in the latter half of the XX. century, it is ostensibly about a technical matter — scholarships and the recognition of credits from foreign universities — but at its heart, it is a peace project.

Corradi recounts a story from a preparatory meeting of French and Italian rectors in 1969:

Professor Contini of the University of Florence was not at all pleased with the proposal and declared that “the draft needed to be examined carefully, that what was requested of the group of experts was a lengthy and complex task, etc.”

But when Corradi explained that the proposal was not really about curricula or credits, but rather about peace and international understanding, he immediately changed his tune. He turned to his colleagues and said that the scheme should be approved quickly, and that any wrinkles could be ironed out later.

This kind of approach can be seen over and over again in the post–WWII decades, when those involved had firsthand experience of war.

When I, as a modern person, see a tricky political problem, my intuition, honed in the recent decades, tells me that the solution will be slow and painful, that the participants will engage in backstabbing, blackmail, and the trading of favours, that we’ll end up, at best, with a watered-down version of what was originally intended, and that, most likely, there isn’t enough political will to accomplish anything at all.

And then I look back at the Europeans of 1950s or 1960s and observe how, when peace is mentioned, they simply set their concerns and mutual disagreements aside and do the right, if unorthodox, thing.

Sadly, the generations with personal experience of war have passed away, and that implicit, unspoken mutual understanding is now gone.

During Brexit, UK has dropped out of the scheme, with the government claiming it was too expensive. But it was clearly part of the broader effort to detach Britain from the EU institutions. And pointing out that it’s a peace project and that even EU’s frenemies, such as Turkey and Serbia, were taking part haven’t made any difference.

Not that the EU itself is blameless in this regard. When Switzerland voted in a referendum in 2014 to introduce immigration quotas, the Union showed that it was willing to weaponize the peace project for political ends and kicked Switzerland out of the scheme in response.

***

Back to the social engineering though.

Despite what Umberto Eco said, Erasmus seems to work a bit differently, at least according to the anecdotes I’ve had a chance to hear.

In fact, the Catalan boy goes to study in Belgium, but he doesn’t make any local friends. They are speaking Flemish among themselves and he has no idea what they are talking about. Also, Europe still carries a certain aristocratic air. Unlike in the United States, it really matters whether you were born somewhere and have spent your whole life there. If that’s not the case, everyone’s going to be friendly and helpful, but you’ll remain an outsider.

Yet, the boy befriends other Erasmus students just as eager for company as he is. Italians, Greeks, Lithuanians. He falls in love with a Polish girl, marries her and they settle in Berlin together and speak English at home.

Which, in the end, is probably even better outcome than what was originally intended.

***

And speaking of social engineering: Yes, this is exactly how you do it!

Substantial portion of students actually does want to spend some time abroad. It’s no different from the Western European marriage pattern, where young people left their parental homes to work as servants, farmhands, or apprentices before they married and set up their own households.

The much-maligned idea of social engineering, in this case, doesn’t mean forcing people to do something they don’t want to do. It means removing the obstacles that prevent them from doing what they already want.

Before Erasmus, studying abroad was seen as having fun rather than as serious academic work, something to be punished rather than rewarded. Universities were reluctant to recognize studies completed elsewhere. Erasmus, with its credit transfer system, changed that and thus unleashed a massive wave of student exchanges.

***

The name “Erasmus” is an acronym, but it was clearly chosen to remind us of Erasmus of Rotterdam, the model travelling scholar. Erasmus spent his life moving between the Netherlands, France, England, Italy, the Holy Roman Empire and Switzerland and thus makes a perfect mascot for the programme.

But Erasmus was also a citizen of what he called respublica litteraria and what later became the Republic of Letters, a long-distance network of intellectuals connected through the exchange of letters and, yes, actual travel, something that was an indispensable precursor to the Enlightenment and the Scientific Revolution.

One can think of it as a two-pronged strategy: Letters kept the network among the intellectual elites alive. Travel created new nodes in the network, meetings, collaborations, and shared projects. Professors often recommended promising students to each other, or engaged in master-disciple relationships, such as Tycho de Brahe with Johannes Kepler or Galileo with Evangelista Torricelli.

Which makes me wonder about how the above applies to the modern world.

Today’s blogosphere is sometimes compared to the old Republic of Letters and not without merit: it enables rapid exchange of ideas between people that would otherwise never meet each other. And that’s a great thing.

When it comes to travel though, the state of affairs is somewhat different. The cheap travel of today makes it easy for people to meet in person for a day or two. But at the same time, it makes long stays, needed for deeper collaborations, that were once a necessity, less common.

It’s fun to imagine, say, Matt Yglesias, spending a year in Europe and writing about European affairs. But I don’t see that happening. (Although progress-minded philanthropists could find the idea of sponsoring such intellectual insemination via long-term mutual exchanges interesting to toy with.)

In the meantime, there’s this huge beast of Erasmus programme, waiting to be taken advantage of. We may complain that there are no progress-minded people in Eastern Europe, but at the same time thousands of young people from the region travel abroad each year to study. How hard would it be to steer the promising few towards specific destinations? Presumably those with an established progress community, with the prospect, that after a year spent abroad they will return home and spread the word further?

***

Europeans take Erasmus for granted. They are rarely aware that nothing quite like it exists elsewhere. People from other parts of the world, meanwhile, often don’t know about it at all. And if they do, they see it as a dull, technocratic, typically European matter. Which, I think, is a shame.